Ok ok, my personal Life of a Hostess isn’t really all that secret, but as someone who truly believes that trash TV is the cultural height of our evolution, I absolutely could not pass on this opportunity of a title. I am however an actual hostess, always have been, always will be. Although since moving back to Vienna about 1.5 years ago, I did kind of hang my apron up in the cupboard a bit too much, let it become dusty. I partly blame the fact that we have a wonderful flat far out in the 18th district, making it not the ideal location for guests to gather, but also the fact that for the first time in my life, most of my friends have real jobs and families. Living in London, my home for almost 10 years after leaving Vienna as a 19-year-old, we always had time for dinner parties: we didn’t have traditional 9–5s, no one had family they had to visit on weekends, we were all kind of just living in London and had each other, our little pack of friends, who truly have become more of a family.

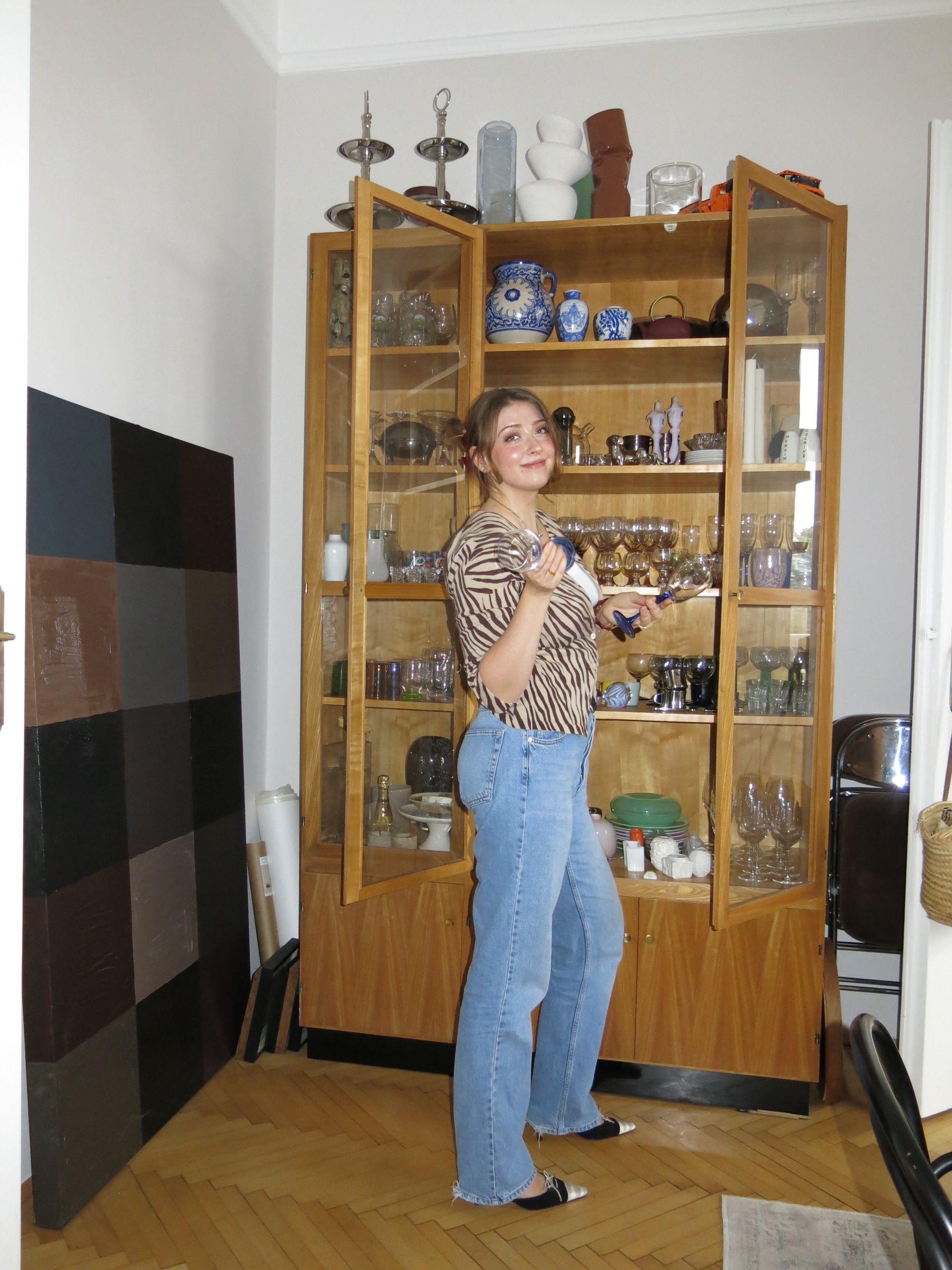

Me and my Glassware

Setting a Table is my Olympic Sport

I hate praising myself, but I did throw damn good dinner parties. They have become somewhat of my signature thing, especially Christmas. It got to the point where I had to buy a second table, another couple of sets of chairs and more glasses than a single-person household should ever have the need to own. Hosting is a mysterious art, people praise you for your talent, which all just comes down to pure stress, spreadsheets and fast problem-solving. I don’t think I ever had a dinner party where I didn’t have a 5pm meltdown with guests arriving at 7pm. Hosting is basically 50% hospitality, 50% theatre, and 10% worrying whether the bread is still warm. Yes, that’s 110%. Hosting runs on emotional maths, not logical maths.

My dinner party villain origin story is a long one, but also really short: my parents were always the hosts. People say I might go overboard at my dinners, but they never dined at my dad’s (my mum and I always just were the sous chefs of his cooking enterprise, never the first hands). He manages to invite people over for a casual evening and we have to talk him down to six courses, because initially, it was meant to be eight. No consideration at all that a normal human being cannot possibly eat eight full portions, not even himself. It’s more about the love language and thought than, again, logic.

London then finally gave me my own stage for hosting, and I quickly realised that the training my dad gave me was very valuable: I actually am a really good cook, which is like half the work done already for a dinner party. It comes naturally for me to even create my own recipes, or just look at an image of a dish and know exactly how it’s done, or at least, how I’d do it. And soon, somewhere between my third Christmas dinner party and my seventh time buying more chairs and seriously considering moving to a bigger flat just to get a bigger table, I realised I had become… a hostess. Not the casual ‘come by if you’re around’ kind, no, a full-blown, apron-tying, seating-chart-drawing, playlist-editing creature who thinks about lighting and butter ratios with the seriousness of a neurosurgeon. Hosting became my medium. Some people paint. Some compose sonatas. I arrange people around a table and hope magic happens between the candle wax and the crumbs.

Salon Todesco

Where Conversation becomes Culture

Vienna, of course, was always big on hosting. The place where the dining table was never just a piece of furniture, but a quiet ministry of culture, politics and gossip. Long before anyone coined the word “networking”, people here had already mastered the art of persuading, seducing and educating each other over dinner, or at least, over wine. In the late 18th and early 19th century, Fanny von Arnstein gathered half the intellectual map of Europe in her Palais on the Hoher Markt: diplomats coming straight from negotiations, Beethoven testing a new movement at the piano, aristocrats and reformers arguing about Napoleon between courses. Her dinners weren’t soirées, they were soft power. She was the vision of what salons would become.

A century later, Berta Zuckerkandl turned her own living room into the unofficial headquarters of Viennese modernism. Klimt, Schnitzler, Mahler, the early Secessionists, they all sat on her sofas, balancing coffee cups while deciding what the future of art should look like. From the outside it was a salon. In reality, it was a laboratory. The city’s most radical aesthetic ideas were developed the way most ideas actually are: at night, with too much smoke in the air and probably someone arguing that the proportions of the new poster (or doormats?) for the Secession were all wrong. (Imagine these people would have had social media. The Stories? The FOMO? Unbelievable.)

Schubert playing at a Viennese Salon by J. Schmidt

Even the supposedly quiet Biedermeier era in Vienna had Caroline Pichler hosting disciplined literary evenings where poetry readings mattered as much as the main courses, and where debate stayed civilised even when the subtext was anything but. Vienna’s history is basically a kitchen story: every cultural moment seems to have begun in a room too small for its ambition, with chairs borrowed from the neighbour and one woman orchestrating the chaos with the grace of a conductor.

And that’s the part that always fascinated me: the hostess is invisible, yet everything depends on her. She doesn’t get the credit for the painting, the novel, the treaty, the new manifesto that developed at her gathering, but without her table, none of these people would have met. It’s probably what is so fascinating for me, as I am usually the last person who’d want attention, but still like orchestrating everything. The meal is the main act, not me, but somehow, I was part of the meal.

Doing what she does best, Serving (Food)

Obviously, my dinner parties are not kick-starting the next Secession (although my candle and wine budget sometimes suggests I’m trying). But I think there is something powerful in the idea that a living room can change people, even if it’s just changing how they feel for one evening, how they connect with friends, how they carry their week. Vienna taught me that hosting is a cultural practice, not just a hobby. It’s a micro-institution that only needs bread, chairs and a slightly delusional belief that the right mix of people will become a moment.

Our Salons

Which is of course exactly what we are trying to do with our own salons. To restart this movement of inspiration, of conversation, of cultural movement. The classic Viennese salon was hosted by women for a very simple reason: women were excluded from the official cultural stage. They could not run universities, sit in parliament or direct theatres, but they could set a table. And they used this so-called domestic privilege as a cultural instrument. The hostess curated the room like others curate exhibitions: she chose the guests, she guided the conversation, she balanced personalities like one balances wine pairings. It wasn’t accidental. It was work. Invisible, unpaid work, but influential.

The salons disappeared when cafés, newspapers and politics moved to other rooms, or when women finally entered those rooms themselves. But what vanished with them was the intimacy of ideas: the slow persuasion that happens only when people sit close, listen and share food, and also a lot of wine.

The only thing left to do? Sign up to one of our Salons,

xx, Ellie

About the author

Eleonore Marie Stifter - Resident Viennese. Writes about culture, taste, and the art of complaining beautifully.